Take a photo of a barcode or cover

Hoop ellende. Het mooiste vind ik de persoonlijke zoektocht van de schrijfster en de ontmoetingen met verre familieleden. De verrassende teleurstellende ontmoeting met een vervelende nicht, de vertwijfeling of de speurtocht wel zo'n goed idee was. Het boek deed me verder denken aan 'Zulajka opent haar ogen' van Guza Jacina en 'Het achtste leven' van Nino Haratischwili, ook twee boeken waarin een lawine aan rampzalige gebeurtenissen de hoofdpersonen overweldigt. Verkrachtingen, politiek geweld, verbanningen, schrijnende armoede, liefdeloosheid. Door het boek snapte ik er meer van hoe de Russische revolutie van gegoede burgers kansloze, verdachte mensen maakte. En dat de emotie 'zo, ben je zelf ook eens arm' te eenvoudig is. De moeder van Natascha maakte een einde aan haar leven, maar na het lezen van het boek vraag je je alleen af waarom ze dat niet veel eerder heeft gedaan en waarom andere mensen eigenlijk wel doorleven.

Honestamente no creo que haya tenido que ser tan largo, a mi no logró transmitirme ningún sentimiento, pero me queda claro que fue catártico y necesario para la autora.

Le rescato lo que aprendí de Ucrania y los países del Este, sin embargo no es algo que el internet no te proporcione.

Definitivamente no es mi género favorito

Le rescato lo que aprendí de Ucrania y los países del Este, sin embargo no es algo que el internet no te proporcione.

Definitivamente no es mi género favorito

Hartverscheurend en indrukwekkend verhaal van een dochter, Natascha Wodin, die op zoek is naar meer informatie over haar moeder. Met slechts enkele foto's en documenten weet ze, met behulp van vele anderen, haar familiegeschiedenis te ontrafelen. En dat is een bijzonder treurig verhaal, maar wel prachtig opgeschreven. Het heeft me enorm geraakt.

Wodin tells intimate stories of different lives lived in the past age by uncovering and narrating the history of her family. The first stories feel cold and factual, dealing mostly with distant relatives. But as the stories come closer to the life of Wodins mother, the facts get supplemented with what she heard and fantasized about her family as a child. In the final part history is not told from books and letters but from memory, placing the drama of one family into the grand perspective of previous generations and historical context.

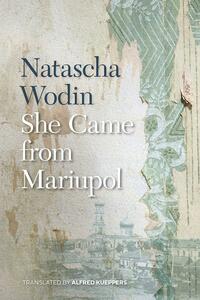

In She Came From Mariupol, Natascha Wodin (1945) shares her search for her mother’s past, which was long hidden from her, while reflecting on how it resonates in her own life. Despite some stylistic shortcomings, I was deeply moved and impressed by the story, which demonstrates the extent to which people are subjected to circumstances and politics, as well as the consequences of forced displacement.

Of the four parts, only the first one didn’t fully satisfy me. Wodin’s attempt to uncover more about her mother, who committed suicide when the author was just 10, is described in excessive detail, yet in the end, she owes most of her findings to an overenthusiastic stranger. That said, what emerges is so fascinating that putting the book down was never an option. The story of her mother’s side of the family is gut-wrenching, poignant, and unimaginable. It proved to be a distressing yet rewarding reading experience.

The following parts are must-reads. First, Wodin revisits the written memoirs of her aunt Lidia, who – coming from an impoverished noble family – witnessed the Russian Revolution, the arrival of the Red Army, and the total anarchy in the Soviet Republic of Ukraine. Some of the details make [b:1984|56196795|1984|George Orwell|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1612999498l/56196795._SY75_.jpg|153313] seem like a children’s tale. The author then tries to recount her mother’s life, born in 1920 in Mariupol, using both public sources and her own imagination. This story covers Operation Barbarossa in 1941, the raids to deport ‘Ostarbeiter’ to Germany, the scorched earth tactics as the Nazis retreated, and, finally, the life of Ukrainians as second-class citizens in Germany. In the final part, Wodin reflects on memories of her own youth in a camp for displaced persons, where poverty and the traumas of the past play a profound role.

While reading, I was reminded of [b:Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China|1848|Wild Swans Three Daughters of China|Jung Chang|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1440643710l/1848._SX50_.jpg|2969000] by Jung Chang, due to the intense yet intimate depictions of a gruesome past, and [b:The Son and Heir|53832625|The Son and Heir A Memoir|Alexander Münninghoff|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1591327935l/53832625._SY75_.jpg|43345478] by Alexander Münninghoff, whose journalistic work remains unmatched. While Wodin’s style might not always stand out, her novel certainly made an impression on me.

Altijd weer, de keerzang van mijn kinderjaren: ‘Als je gezien had wat ik heb gezien…’

Of the four parts, only the first one didn’t fully satisfy me. Wodin’s attempt to uncover more about her mother, who committed suicide when the author was just 10, is described in excessive detail, yet in the end, she owes most of her findings to an overenthusiastic stranger. That said, what emerges is so fascinating that putting the book down was never an option. The story of her mother’s side of the family is gut-wrenching, poignant, and unimaginable. It proved to be a distressing yet rewarding reading experience.

The following parts are must-reads. First, Wodin revisits the written memoirs of her aunt Lidia, who – coming from an impoverished noble family – witnessed the Russian Revolution, the arrival of the Red Army, and the total anarchy in the Soviet Republic of Ukraine. Some of the details make [b:1984|56196795|1984|George Orwell|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1612999498l/56196795._SY75_.jpg|153313] seem like a children’s tale. The author then tries to recount her mother’s life, born in 1920 in Mariupol, using both public sources and her own imagination. This story covers Operation Barbarossa in 1941, the raids to deport ‘Ostarbeiter’ to Germany, the scorched earth tactics as the Nazis retreated, and, finally, the life of Ukrainians as second-class citizens in Germany. In the final part, Wodin reflects on memories of her own youth in a camp for displaced persons, where poverty and the traumas of the past play a profound role.

While reading, I was reminded of [b:Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China|1848|Wild Swans Three Daughters of China|Jung Chang|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1440643710l/1848._SX50_.jpg|2969000] by Jung Chang, due to the intense yet intimate depictions of a gruesome past, and [b:The Son and Heir|53832625|The Son and Heir A Memoir|Alexander Münninghoff|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1591327935l/53832625._SY75_.jpg|43345478] by Alexander Münninghoff, whose journalistic work remains unmatched. While Wodin’s style might not always stand out, her novel certainly made an impression on me.

Searching for the past of her mother, who committed suicide when she was still a child, and of whom she knows practically only the place of origin, Mariupol, in Ukraine, the author discovers, and tells, an incredible story of social transformation, war and emigration, between the Soviet revolution and the Nazi invasion. The number of events, twists and turns, and pain, collected in this book is decidedly impressive, and the writing, simple and not at all emphatic, only increases the impression it makes on the reader a hundredfold.

A book to be read, absolutely.

A book to be read, absolutely.

Finde es hart sowas persönliches zu bewerten. Meine Leseerfahrung war aber gemischt: einerseits war es faszinierend zu lesen, wie die eigenen Vorfahren gefunden werden. Ein sehr guter Roman, um das "displacement" nach dem 2. Weltkrieg von Ukrainer*innen zu verstehen, die furchtbare Situation in Deutschland. Daher: wichtig, gut, notwendig.

Was mich sehr störte waren die teilweise etwas eskalierenden Mutmaßungen. Natürlich müssen kleine Fitzelchen von Informationen mit Leben gefüllt werden, aber ich fand es teilweise sehr dünn. Auch das Ende fand ich sehr enttäuschend in dem Sinne, dass keinerlei Abschluss kam. Es endete einfach irgendwie.

Was mich sehr störte waren die teilweise etwas eskalierenden Mutmaßungen. Natürlich müssen kleine Fitzelchen von Informationen mit Leben gefüllt werden, aber ich fand es teilweise sehr dünn. Auch das Ende fand ich sehr enttäuschend in dem Sinne, dass keinerlei Abschluss kam. Es endete einfach irgendwie.

challenging

dark

sad

tense

slow-paced

dark

emotional

informative

sad

medium-paced

Desolador. Empecé a leer este libro tres días después de la invasión rusa en Ucrania y lo he terminado poco después de que Mariúpol haya quedado, de nuevo, destruida. Ha sido una lectura difícil por lo crudo y descarnado de la guerra y los totalitarismos.