Take a photo of a barcode or cover

dark

reflective

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Complicated

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

reflective

medium-paced

puzzling over this one - two stories in some kind of contrast. One the story of married woman with two children, who takes off with another man in some attempt to escape societies expectations. We see mostly his perspective and his attempts to make things work. They other is the story of a convict who gets lost during the 1927 flood, and floats down the Mississippi Huck like, but instead of Jim, he's with a pregnant women nearing labor. The men are the story and they both pursue their own logic, with their own principles, and stick to them.

There are interesting elements. And I got caught up in it in places, escapes the accidentally escaped convict. But I'm left feeling maybe this one wasn't thought through all the way, maybe it doesn't work. Of course, I don't really know that I read it correctly.

There are interesting elements. And I got caught up in it in places, escapes the accidentally escaped convict. But I'm left feeling maybe this one wasn't thought through all the way, maybe it doesn't work. Of course, I don't really know that I read it correctly.

challenging

dark

sad

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

I went into this completely blind. I've read about 9 of Faulkner's novels, along with all of his short stories. The Wild Palms was so much more than I was expecting. It is Faulkner, which I love, but it was so much more varied in location then most Faulkner. It addressed quite modern issues (abortion, incarceration, etc).

I enjoyed it so much more than I expected.

I enjoyed it so much more than I expected.

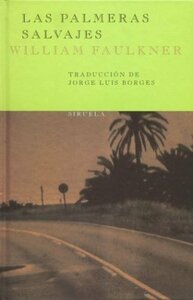

I’m not sure where to begin when talking about The Wild Palms. Perhaps by clarifying that The Wild Palms is the publisher’s chosen name for If I Forget Thee, Jerusalem, Faulkner’s preferred title, and that it is also one of two intertwined stories in the book published under that title. A friend insisted that I read it, that it would probably become my new favorite book, but that I also might want to throw it against a wall when I finished. As usual, he was annoyingly right.

The Wild Palms was my first Faulkner, despite my degree in English and my two Southern-born-and-educated advisers and my proclivity for mid-century male authors (see also: Hemingway, Durrell, Greene). As an educated and enlightened woman in this day and age, I know that I should have strong feelings about the rampant (perceived or actual) misogyny in the works of these authors. I know. Let’s just set that aside for now because you know what? I don’t want to hear it. This isn’t about what I should think or feel. It is about what I am or did or do think or feel.

And that was completely devastated. I started the book on a rainy Friday night when Rachel and I wanted to be alone together, her at one end of the living room with video games and the dog, me curled up with my book and a glass of wine and the cool breeze. I was leaving Ann Arbor in four days, and my copy was checked out from the library, adding an extra urgency to the read. I went to bed early, woke early, and finished the first 70 pages by 7am, turning back into my pillow for a good, wrenching cry.

“It doesn’t die; you’re the one that dies. It’s like the ocean: if you’re no good, if you begin to make a bad smell in it, it just spews you up somewhere to die. You die anyway, but I had rather drown in the ocean than be urped up onto a strip of dead beach and be dried away by the sun into a little foul smear with no name to it, just This Was for an epitaph.”

I had things I needed to do – it was my last weekend in town – but I spent part of Saturday morning walking around in a daze, the mood heightened by the fine mist and the fact that I forgot my wallet at home, thus preventing me from buying coffee until far too late in the day for me to be actually functional. I felt like that U2 song whose video provided one of my earliest impressions of alternative music and memories of MTV from a summer visit to my grandparents, when I would sneak downstairs while they napped to watch cable in Grandpa’s huge naugahyde chair. The hugeness of the chair and the significance of the video have both diminished over time, as will, I suspect, the memory of the numbness of that morning, though there have been other mornings like it that have stuck with me for years and years.

“It’s what we have come to work for, got into the habit of working for before we knew it, almost waited too late before we found it out.”

In the titular story, a couple turns their back on all of the things society tells us to value – children, careers, friends, stability – for love, for love only, for love always.

“Listen: it’s got to be all honeymoon, always. Either heaven, or hell: no comfortable safe peaceful purgatory between for you and me to wait in until good behavior or forbearance or shame or repentance overtakes us.”

Do I even need to tell you that there can’t possibly be a happy ending? “That story ends very badly for all involved, you know.” “Don’t all the good ones?” And then there’s this, where I am right now, drinking bourbon in the back room of my new apartment in Pilsen, listening to the whistle of trains in the distance, scanning for the moon against the night sky.

“You must do it in solitude and you can bear just so much solitude and stil live, like electricity. And for this one or two seconds you will be absolutely alone: not before you were and not after you are not, because you are never alone then; in either case, you are secure and companioned in a myriad and inextricable anonymity: in the one, dust from dust; in the other, seething worms to seething worms.”

The theorists would tell me that there is no meaning outside the text. The theorists would tell me that my reading is contextually bound. Most of the time I feel like the theorists are full of shit, but this one time, I’ll buy it. I’ll buy it because this story resonated with me in ways I didn’t anticipate. Because I recognized myself, my experience, my fears and desires in both the normalcy the couple fled, and the recklessness with which they embraced the impossible. Because I was thankful for the (slight) reprieve offered by Old Man, the story told in alternating chapters – of a convict facing similarly inexorable though completely different circumstances, choices, and actions. Because I was thankful to finish the book on a flight back from DC, surrounded on all sides by people, unable to completely lose my shit as I would have otherwise. Because I was thankful to finish the book at the end of the flight and on the eve of two extremely long, extremely draining days when I wouldn’t have time to read anything else, allowing the book to rest in my mind and on my heart in the same way that you might savor the first taste of something amazing, in the way that a first (or last) kiss lingers on your lips long after the physical sensation has passed into memory.

“Because if memory exists outside of the flesh it wont be memory because it wont know what it remembers so when she became not then half of memory became not and if I become not then all of remembering will cease to be. – Yes he thought Between grief and nothing I will take grief.”

This is the fourth of at least 10 books that I plan to read in the next year for my friend Mark’s 2/3 Challenge.

The Wild Palms was my first Faulkner, despite my degree in English and my two Southern-born-and-educated advisers and my proclivity for mid-century male authors (see also: Hemingway, Durrell, Greene). As an educated and enlightened woman in this day and age, I know that I should have strong feelings about the rampant (perceived or actual) misogyny in the works of these authors. I know. Let’s just set that aside for now because you know what? I don’t want to hear it. This isn’t about what I should think or feel. It is about what I am or did or do think or feel.

And that was completely devastated. I started the book on a rainy Friday night when Rachel and I wanted to be alone together, her at one end of the living room with video games and the dog, me curled up with my book and a glass of wine and the cool breeze. I was leaving Ann Arbor in four days, and my copy was checked out from the library, adding an extra urgency to the read. I went to bed early, woke early, and finished the first 70 pages by 7am, turning back into my pillow for a good, wrenching cry.

“It doesn’t die; you’re the one that dies. It’s like the ocean: if you’re no good, if you begin to make a bad smell in it, it just spews you up somewhere to die. You die anyway, but I had rather drown in the ocean than be urped up onto a strip of dead beach and be dried away by the sun into a little foul smear with no name to it, just This Was for an epitaph.”

I had things I needed to do – it was my last weekend in town – but I spent part of Saturday morning walking around in a daze, the mood heightened by the fine mist and the fact that I forgot my wallet at home, thus preventing me from buying coffee until far too late in the day for me to be actually functional. I felt like that U2 song whose video provided one of my earliest impressions of alternative music and memories of MTV from a summer visit to my grandparents, when I would sneak downstairs while they napped to watch cable in Grandpa’s huge naugahyde chair. The hugeness of the chair and the significance of the video have both diminished over time, as will, I suspect, the memory of the numbness of that morning, though there have been other mornings like it that have stuck with me for years and years.

“It’s what we have come to work for, got into the habit of working for before we knew it, almost waited too late before we found it out.”

In the titular story, a couple turns their back on all of the things society tells us to value – children, careers, friends, stability – for love, for love only, for love always.

“Listen: it’s got to be all honeymoon, always. Either heaven, or hell: no comfortable safe peaceful purgatory between for you and me to wait in until good behavior or forbearance or shame or repentance overtakes us.”

Do I even need to tell you that there can’t possibly be a happy ending? “That story ends very badly for all involved, you know.” “Don’t all the good ones?” And then there’s this, where I am right now, drinking bourbon in the back room of my new apartment in Pilsen, listening to the whistle of trains in the distance, scanning for the moon against the night sky.

“You must do it in solitude and you can bear just so much solitude and stil live, like electricity. And for this one or two seconds you will be absolutely alone: not before you were and not after you are not, because you are never alone then; in either case, you are secure and companioned in a myriad and inextricable anonymity: in the one, dust from dust; in the other, seething worms to seething worms.”

The theorists would tell me that there is no meaning outside the text. The theorists would tell me that my reading is contextually bound. Most of the time I feel like the theorists are full of shit, but this one time, I’ll buy it. I’ll buy it because this story resonated with me in ways I didn’t anticipate. Because I recognized myself, my experience, my fears and desires in both the normalcy the couple fled, and the recklessness with which they embraced the impossible. Because I was thankful for the (slight) reprieve offered by Old Man, the story told in alternating chapters – of a convict facing similarly inexorable though completely different circumstances, choices, and actions. Because I was thankful to finish the book on a flight back from DC, surrounded on all sides by people, unable to completely lose my shit as I would have otherwise. Because I was thankful to finish the book at the end of the flight and on the eve of two extremely long, extremely draining days when I wouldn’t have time to read anything else, allowing the book to rest in my mind and on my heart in the same way that you might savor the first taste of something amazing, in the way that a first (or last) kiss lingers on your lips long after the physical sensation has passed into memory.

“Because if memory exists outside of the flesh it wont be memory because it wont know what it remembers so when she became not then half of memory became not and if I become not then all of remembering will cease to be. – Yes he thought Between grief and nothing I will take grief.”

This is the fourth of at least 10 books that I plan to read in the next year for my friend Mark’s 2/3 Challenge.

Didn't care too much for the writing style, it just made me confused and forget what the point was. The story didn't draw me in, either.

A very dense but electrically articulate novel. Not where I'd recommend starting with Faulkner, this one you've got to (like the southerners) have faith trusting he will reward you with worthwhile passages if you work through the swampy moments. The two parallel stories are not inextricably linked but they follow 2 gentleman who despite misfortune are trying to do the right thing. There is NO hope, no delusions of grandeur, they live in the story moment by moment. They don't have an American dream, they're not expecting their lives to change drastically, but neither are they feeling like they're in the most dire circumstances yet. They teeter on a balance and seem resigned to whatever comes their way chancing their luck as they move through time.

"Between grief and nothing I will take grief."

All the things one would expect from Faulkner are present here: depressing Southern locales, hopelessness, and rambling, incisive prose.

The two interwoven tales revolve around a common theme... if you can really call it that. Set in the poverty of the South in the 1930s, the characters do not pursue modern aspirations like happiness, self-fulfillment or even peace. They don't hope. They don't dream.

Harry and Charlotte's romance is hopeless almost from word one, and they both know it. Harry just kind of falls backwards into the relationship, taking as it goes, accepting that they have an expiration date, but just existing in the moment while they can. This is the kind of doomed love that Hollywood often flirts with, but here it is firmly grounded in its time.

The story of the tall convict is one more about duty than anything else. In jail since before he was ever really old enough to try and find an above-the-board way in the world, he has never really had a chance to prove or even discover his character. But when asked to paddle a boat out to save a pregnant woman during a great flood, he spends more than a month a half executing his task. He cares for the woman, navigates the uncertain and shifting waters of a flooded Mississippi delta, never losing sight of his duty and never even considering escape.

Both stories tap into a style and mode of living that I think is closer to the true human experience of the last 10,000 years. This aspiration, naval-gazing time that we live in is not long for this world. We're allowed to indulge in Romance because we don't have to spend so much of our time and energy just trying to survive.

But when you live closer to the edge, the principle choice is much closer to the bone. It's really whether to live or not to live. And both characters show the frenzy with which man will cling to grief when the only other choice is nothing.

Welcome to the "Perfect Days" book club!

I held this book at the library the same night we arrived home from seeing "Perfect Days" at the theater. It's the first book we see Hirayama trying to read at night until he ultimately can't keep his eyes open any longer. When I started reading it, I thought, "no wonder he can't stay awake for this." I try to read classics but often just can't get into the old language and the way they are written like baseball (too long, because there's nothing better to do.) Color me nervous when I found this novel was also written in stream of consciousness. Another literary style I just can't get into. And yet... I really liked this book.

This novel's been around for 84 years, but I will still warn that what follows includes spoilers.

You have to be ready to hear every slur for every kind of person under the sun, many of which are so old, I didn't know who we were insulting. I learned that "hunky" used to be an ethnic slur for Slavic and Hungarian immigrants, but now it just means a sexy man, so I guess that worked out for them in the end. The story starts to get pretty juicy and it's kind of fun just living in these guys' heads trying to figure out what the heck is happening. Slowly you piece things together. While I don't typically like stream of consciousness, it felt at home in this novel as it was full of that early 1900s melodrama that's so much fun- where it's just a lot of people being in love in over the top ways.

Yesterday I read far enough to find that the reason the woman in our story looked so sick in the opening is because she had an accidentally botched abortion by her lover- a doctor. That was a surprising turn to find in a 1939 novel, but there was also the uncanny timing of my reading it. The very evening before, Coops and I put on the State of the Union in which Biden said he was creating a task force for women's health, he wanted to enshrine reproductive rights, and many of Jill Biden's guests were women that had to flee their home states to get lifesaving abortions. So this novel really hit like an emotional hammer with that juxtaposition of women losing their lives 84 years ago and still having to fight for those lives today. Heavy, am I right? I'll leave you with this quoted section that I found to be very beautiful:

"Your first attempt?"

"No. Second."

"Other one come off? But you wouldn't know."

"Yes. I know. It did."

"Then how do you account for this failure?" He could have answered that: I loved her.

I held this book at the library the same night we arrived home from seeing "Perfect Days" at the theater. It's the first book we see Hirayama trying to read at night until he ultimately can't keep his eyes open any longer. When I started reading it, I thought, "no wonder he can't stay awake for this." I try to read classics but often just can't get into the old language and the way they are written like baseball (too long, because there's nothing better to do.) Color me nervous when I found this novel was also written in stream of consciousness. Another literary style I just can't get into. And yet... I really liked this book.

This novel's been around for 84 years, but I will still warn that what follows includes spoilers.

You have to be ready to hear every slur for every kind of person under the sun, many of which are so old, I didn't know who we were insulting. I learned that "hunky" used to be an ethnic slur for Slavic and Hungarian immigrants, but now it just means a sexy man, so I guess that worked out for them in the end. The story starts to get pretty juicy and it's kind of fun just living in these guys' heads trying to figure out what the heck is happening. Slowly you piece things together. While I don't typically like stream of consciousness, it felt at home in this novel as it was full of that early 1900s melodrama that's so much fun- where it's just a lot of people being in love in over the top ways.

Yesterday I read far enough to find that the reason the woman in our story looked so sick in the opening is because she had an accidentally botched abortion by her lover- a doctor. That was a surprising turn to find in a 1939 novel, but there was also the uncanny timing of my reading it. The very evening before, Coops and I put on the State of the Union in which Biden said he was creating a task force for women's health, he wanted to enshrine reproductive rights, and many of Jill Biden's guests were women that had to flee their home states to get lifesaving abortions. So this novel really hit like an emotional hammer with that juxtaposition of women losing their lives 84 years ago and still having to fight for those lives today. Heavy, am I right? I'll leave you with this quoted section that I found to be very beautiful:

"Your first attempt?"

"No. Second."

"Other one come off? But you wouldn't know."

"Yes. I know. It did."

"Then how do you account for this failure?" He could have answered that: I loved her.

That was pretty powerful. Not my favorite Faulkner, but really something (and lots to write about).