Take a photo of a barcode or cover

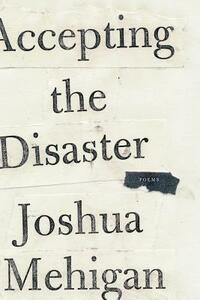

Accepting the Disaster, Joshua Mehigan's second collection of poems, hit bookstore shelves earlier this week, a solid decade after the publication of his quietly accomplished 2004 debut (The Optimist). In the interval, new poems and essays by Mehigan have frequently enlivened the pages of Poetry Magazine, giving hints as to what this long-awaited second collection might contain. Recent magazine publications like the 2011 tour-de-force essay "I Thought You Were a Poet," an intimate and often-hilarious exploration of the relationships between poetry and mental illness, filled readers with high expectations that Mehigan's second book would break new ground by embracing a franker approach to mental illness and other taboo topics.

It would be hard for any book to live up to such high expectations. Perhaps this is why so many poets succumb to the cringe-inducing mistake of letting no more than one or two years elapse between the publication of their first book and their second. Mehigan, at least, had the wisdom not to release Accepting the Disaster into the world until it was full-fledged. The result is a very fine 76-page book that feels completely finished, mature, apotheotic.

In my Goodreads review of The Optimist last year, I wrote: "Mehigan wields iambic pentameter with the effortless dexterity of a grandmother knitting in the darkness of a movie theater." I am so proud of having come up with that simile that I'll say it again here. Mehigan's formal mastery is simply breathtaking. His sonnets are so perfectly executed that you hardly notice they are sonnets. His triolets ("The Crossroads," "Cold Turkey") are virtually the only truly successful triolets I have ever seen. Even as he excels at writing eight-line poems, he succeeds equally well at longer forms: the two most brilliant and original poems in this collection are the two longest ones, the title poem (a wide-ranging satirical poem that could be read as a damning indictment of our society's slowness at accepting the reality of climate change) and "The Orange Bottle" (sadly the only poem in this collection that directly addresses the topic of mental illness, but a masterpiece at that).

Mehigan is a man of many diverse interests: this collection contains elegies to both Michael Jackson and Janis Joplin, for Christ's sake. Still, most of the poems in the book are concerned with small-town American life, the humanity beneath its veneer of banality, the menace behind its facade of passive benignity (If only one poem in this book achieves immortality, I predict it will be the chilling "Down in the Valley", an obliquely told crime story as subtly written as something by Li Po). Mehigan doesn't prettify or romanticize his subjects: his language is stubbornly plain, his metaphors almost clinical in their precision: "the western wall of one far building/turned by the setting sun the color of Mars." The wall was red, made by one celestial body to take on the color of another celestial body: the metaphor tells us not an ounce more, but also not an ounce less. Mehigan delights in understatement; he revels in self-deprecating verbal backtracking. One of his favorite verbal tricks is the tautology, the statement that seems obvious at first glance but reveals deeper layers of meaning upon rereading: "Nothing here ever changes, till it does"; "You might not know it unless you knew"; "A searchlight scanned the heavens and found the heavens." Mehigan has turned the tautology into an art form.

In the end, Accepting the Disaster is like a seismograph. Seismographs are not judged by how good they are at detecting large earthquakes; even a plate wobbling on a shelf is able to do that. Instead, seismographs are judged by how adept they are documenting very small tectonic quivers, earthquakes so minute that people don't even realize they are happening. This book is an exquisitely sensitive seismograph of the human condition.

It would be hard for any book to live up to such high expectations. Perhaps this is why so many poets succumb to the cringe-inducing mistake of letting no more than one or two years elapse between the publication of their first book and their second. Mehigan, at least, had the wisdom not to release Accepting the Disaster into the world until it was full-fledged. The result is a very fine 76-page book that feels completely finished, mature, apotheotic.

In my Goodreads review of The Optimist last year, I wrote: "Mehigan wields iambic pentameter with the effortless dexterity of a grandmother knitting in the darkness of a movie theater." I am so proud of having come up with that simile that I'll say it again here. Mehigan's formal mastery is simply breathtaking. His sonnets are so perfectly executed that you hardly notice they are sonnets. His triolets ("The Crossroads," "Cold Turkey") are virtually the only truly successful triolets I have ever seen. Even as he excels at writing eight-line poems, he succeeds equally well at longer forms: the two most brilliant and original poems in this collection are the two longest ones, the title poem (a wide-ranging satirical poem that could be read as a damning indictment of our society's slowness at accepting the reality of climate change) and "The Orange Bottle" (sadly the only poem in this collection that directly addresses the topic of mental illness, but a masterpiece at that).

Mehigan is a man of many diverse interests: this collection contains elegies to both Michael Jackson and Janis Joplin, for Christ's sake. Still, most of the poems in the book are concerned with small-town American life, the humanity beneath its veneer of banality, the menace behind its facade of passive benignity (If only one poem in this book achieves immortality, I predict it will be the chilling "Down in the Valley", an obliquely told crime story as subtly written as something by Li Po). Mehigan doesn't prettify or romanticize his subjects: his language is stubbornly plain, his metaphors almost clinical in their precision: "the western wall of one far building/turned by the setting sun the color of Mars." The wall was red, made by one celestial body to take on the color of another celestial body: the metaphor tells us not an ounce more, but also not an ounce less. Mehigan delights in understatement; he revels in self-deprecating verbal backtracking. One of his favorite verbal tricks is the tautology, the statement that seems obvious at first glance but reveals deeper layers of meaning upon rereading: "Nothing here ever changes, till it does"; "You might not know it unless you knew"; "A searchlight scanned the heavens and found the heavens." Mehigan has turned the tautology into an art form.

In the end, Accepting the Disaster is like a seismograph. Seismographs are not judged by how good they are at detecting large earthquakes; even a plate wobbling on a shelf is able to do that. Instead, seismographs are judged by how adept they are documenting very small tectonic quivers, earthquakes so minute that people don't even realize they are happening. This book is an exquisitely sensitive seismograph of the human condition.

dark

funny

reflective

Moderate: Forced institutionalization, Schizophrenia/Psychosis

Minor: Mental illness, Medical content

Wish I had liked this more, but it just didn't connect with me. Every once in a while a line or poem would strike me, or open up a bit, but too often the rhyming felt juvenile and the meaning surface-level. Love the central conceit of the book though-- disasters and decay and death and endings.