Take a photo of a barcode or cover

challenging

emotional

informative

reflective

medium-paced

Dated, misogynistic and paternalistic in parts.

Still enjoyed the premise, the language and some very precise and thoughtful moments. Would recommend if the topic is of interest, with some warnings going in.

The essay plus photo format is fab, really enjoyed this aspect.

Still enjoyed the premise, the language and some very precise and thoughtful moments. Would recommend if the topic is of interest, with some warnings going in.

The essay plus photo format is fab, really enjoyed this aspect.

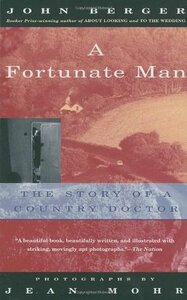

This little piece of non-fiction is stunning. It describes the life of a doctor in rural England and his interaction with his patients. It isn't very traditional. There are several short stories, or even flash-length pieces in there, and the whole book is illustrated with actual photos.

Philosophically, it discusses what it means to be a doctor and to share such intimate secrets with your patients, what it means to heal and what it means to belong to a community.

I think I want to reread this book.

Philosophically, it discusses what it means to be a doctor and to share such intimate secrets with your patients, what it means to heal and what it means to belong to a community.

I think I want to reread this book.

hopeful

informative

reflective

slow-paced

I was very disappointed in this book, which purports to be a portrait of a rural doctor but is actually an excuse for Berger to expostulate on his views on rural ‘peasantry’. Berger is patronising to the patients and you have to wonder how much agency they had in being able to say no to their intimate secrets being spilled and their portraits published. Further all that Berger proclaims superlative in the doctor is unhealthy when viewed retrospectively in light of the doctors suicide which seems unsurprising to the reader but not to Berger.

What a revelation this book was! It's ostensibly a portrait - in words and photographs - of an NHS GP working in a quiet Gloucestershire village. But the doctor's own thoughtfulness, coupled with the writer's sociological description of his role in society at large makes the whole thing feel fantastically deep. It becomes a meditation on what it means to live a full life in an imperfect society. The writer is clearly from a left wing academic tradition, and his viewpoint colours the narrative but not, I think, in a tedious, didactic way. It's direct, concise, and the photographs complement the text beautifully. Definitely recommended.

I would have given five stars if this had been mostly about the photographs (which are superb), and I would have given five stars if this had been mostly about the case studies - both these elements were wonderful. I was also really interested in how Berger saw Sassall's relationship with his patients, how he felt he needed to imagine what it was like to be them, to almost become them, and also the essay on anguish and how it takes us back to childhood.

I understand that all books are a product of the time they're written in, but the first problem for me was how male-centric Berger makes this book, and somehow I wouldn't have expected it of him. When Sassall's patients are discussed as a group they are the foresters - literally those who work with the trees in that part of the world, and male. (The female patients are sometimes mentioned in passing: unmarried girls who come to him when pregnant, women giving birth.) And when Berger compares doctoring with other professions, an artist for example, his examples are male. I simply tired of this after a while.

And secondly I had a bit of an issue with how Berger describes Sassall as so unique and important in the way he goes about his work (perhaps true), but in comparison to an 'average' patient, who 'expects to maintain what he has - job, family home.' I don't believe there was or is an average patient, and I don't believe that there weren't numerous 'foresters' who didn't aspire for something more.

www.clairefuller.co.uk

I understand that all books are a product of the time they're written in, but the first problem for me was how male-centric Berger makes this book, and somehow I wouldn't have expected it of him. When Sassall's patients are discussed as a group they are the foresters - literally those who work with the trees in that part of the world, and male. (The female patients are sometimes mentioned in passing: unmarried girls who come to him when pregnant, women giving birth.) And when Berger compares doctoring with other professions, an artist for example, his examples are male. I simply tired of this after a while.

And secondly I had a bit of an issue with how Berger describes Sassall as so unique and important in the way he goes about his work (perhaps true), but in comparison to an 'average' patient, who 'expects to maintain what he has - job, family home.' I don't believe there was or is an average patient, and I don't believe that there weren't numerous 'foresters' who didn't aspire for something more.

www.clairefuller.co.uk

hopeful

inspiring

reflective

slow-paced

"How is it that Sassall is acknowledged as a good doctor? By his cures? This would seem to be the answer. But I doubt it. You have to be a startlingly bad doctor and make many mistakes before the results tell against you. In the eyes of the layman the results always tend to favour the doctor. No, he is acknowledged as a good doctor because he meets the deep but unformulated expectation of the sick for a sense of fraternity. He recognises them."

I took a lot away from this, on the background stability gifted to us by healthcare workers, and the importance of community and hearing each other — our ailments, our worries, our aches & pains both physical and mental. The photography accompanying was satisfying. The concluding remarks may need another read one day, and I wasn't entirely gripped, but it painted a good picture.

This is a deeply humanistic account of the "value of a life". It is easily one of my favorite books. The knowledge of what human life is worth would, as Berger argues, require a radical transformation of society and a reconstitution of class. More reflections soon... I am so glad to have read this for an anthropology class.

I plan on reading more of Berger's works this summer!

I plan on reading more of Berger's works this summer!

I was recommended this book in a masterclass about writing creative non-fiction by author Dan Richards. It has its flaws but is a small philosophical gem I will return to again and again. The narrative is complemented perfectly with Jean Mohr's black and white photographs. It is hard to satisfactorily summarise this book you will just have to read it!

I was poking around the shelves of books on doctoring when I came across John Berger’s A Fortunate Man – The Story of a Country Doctor. I’d only known Berger from Ways of Seeing, his book on art, and it surprised me that he’d written a portrait of a doctor in rural England. Most of the books I’d read about doctors and medicine were based in large hospital settings – Mass Gen, Mayo Clinic-type settings.

A Fortunate Man is the polar opposite of these – John Sassell chose a remote country practice under the NHS, handling everything from “appendix and hernia operations on kitchen tables”, “delivering babies in caravans”, to treating measles and giving vaccinations. But he is so much more than a medical practitioner. He is a confidant, a therapist and social worker:

“He deals with all emergencies which arise – from serious accidents in the quarries or at harvesting time in the fields, to the despair of a young woman who wants to kill her illegitimate baby or the slow suffering and eventual collapse of a retired vicar who has lost his faith.”

But more than that, Berger describes Sassell as a “witness” who gives his patient recognition – recognition as a unique individual who is simultaneously knowable (and therefore curable). He is also the “clerk of [the community’s] records” who bears witness to their collective lives and inner selves, who “thinks and speaks what the community feels and incoherently knows…the growing force…of their self-consciousness.”

But A Fortunate Man isn’t just about Sassell. It is also about the context in which he operates and Berger’s observations on this front are acute:

“The inarticulateness of the English is the subject of many jokes and is often explained in terms of puritanism, shyness as a national characteristic, etc. This tends to obscure a more serious development. There are large sections of the English working and middle class who are inarticulate as the result of wholesale cultural deprivation. They are deprived of the means of translating what they know into thoughts which they can think. They have no examples to follow in which words clarify experience. Their spoken proverbial traditional have long been destroyed: and, although they are literate in the strictly technical sense, they have not had the opportunity of discovering the existence of a written cultural heritage.

Yet it is more than a question of literature. Any general culture acts as a mirror which enables the individual to recognize himself – or at least to recognize those parts of himself which are socially permissible. The culturally deprived have far fewer ways of recognizing themselves. A great deal of their experience – especially emotional and introspective experience – has to remain unnamed for them. Their chief means of self-expression is consequently through action: this is one of the reasons why the English have so many ‘do-it-yourself’ hobbies. The garden or the work bench becomes the nearest they have to a means of satisfactory introspection.”

A beautifully-written portrait.

A Fortunate Man is the polar opposite of these – John Sassell chose a remote country practice under the NHS, handling everything from “appendix and hernia operations on kitchen tables”, “delivering babies in caravans”, to treating measles and giving vaccinations. But he is so much more than a medical practitioner. He is a confidant, a therapist and social worker:

“He deals with all emergencies which arise – from serious accidents in the quarries or at harvesting time in the fields, to the despair of a young woman who wants to kill her illegitimate baby or the slow suffering and eventual collapse of a retired vicar who has lost his faith.”

But more than that, Berger describes Sassell as a “witness” who gives his patient recognition – recognition as a unique individual who is simultaneously knowable (and therefore curable). He is also the “clerk of [the community’s] records” who bears witness to their collective lives and inner selves, who “thinks and speaks what the community feels and incoherently knows…the growing force…of their self-consciousness.”

But A Fortunate Man isn’t just about Sassell. It is also about the context in which he operates and Berger’s observations on this front are acute:

“The inarticulateness of the English is the subject of many jokes and is often explained in terms of puritanism, shyness as a national characteristic, etc. This tends to obscure a more serious development. There are large sections of the English working and middle class who are inarticulate as the result of wholesale cultural deprivation. They are deprived of the means of translating what they know into thoughts which they can think. They have no examples to follow in which words clarify experience. Their spoken proverbial traditional have long been destroyed: and, although they are literate in the strictly technical sense, they have not had the opportunity of discovering the existence of a written cultural heritage.

Yet it is more than a question of literature. Any general culture acts as a mirror which enables the individual to recognize himself – or at least to recognize those parts of himself which are socially permissible. The culturally deprived have far fewer ways of recognizing themselves. A great deal of their experience – especially emotional and introspective experience – has to remain unnamed for them. Their chief means of self-expression is consequently through action: this is one of the reasons why the English have so many ‘do-it-yourself’ hobbies. The garden or the work bench becomes the nearest they have to a means of satisfactory introspection.”

A beautifully-written portrait.