Scan barcode

A review by abehab

The Fortress: The Great Siege of Przemysl by Alexander Watson

4.0

‘’These peasant soldiers are in death, as in life, anonymous. The empires for which they fell would within just a few years both lie in ruins. Yet the violence unleashed by their war would live on.’'

As far as an amateur history enthusiast, such as myself, is concerned, reading a book written exclusively about a besieged fortress city on the Eastern Front of the first world war is as niche as it gets. I have been intrigued with the history of the siege of Przemyśl, ever since I read my first book on the first world war. In the ensuing years, I read a lot on it, but never dipped into a book solely dedicated to the siege. [b:The Fortress: The Great Siege of Przemysl|52971649|The Fortress The Great Siege of Przemysl|Alexander Watson|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1571267227l/52971649._SX50_SY75_.jpg|68162194], marks the first book I read, primarily written on Przemyśl during the first world war.

Przemyśl was the third-largest fortress city in The Austria-Hungary Empire, after Kraków and Lemberg (Current day Lviv, Ukraine). The siege of Przemyśl, can in actuality be viewed in three separate phases. The First phase (September 18, 1914 - October 9, 1914) is a failed siege by the Russians on the fortress. The Second phase (November 6, 1914 - March 2, 1915) is the longest and much more successful siege undertook by the Tsar’s army. The third and final phase (May 18, 1915 - June 3, 1915) was the relief operation the joint forces of German and Habsburg armies took up against the Russian occupying forces.

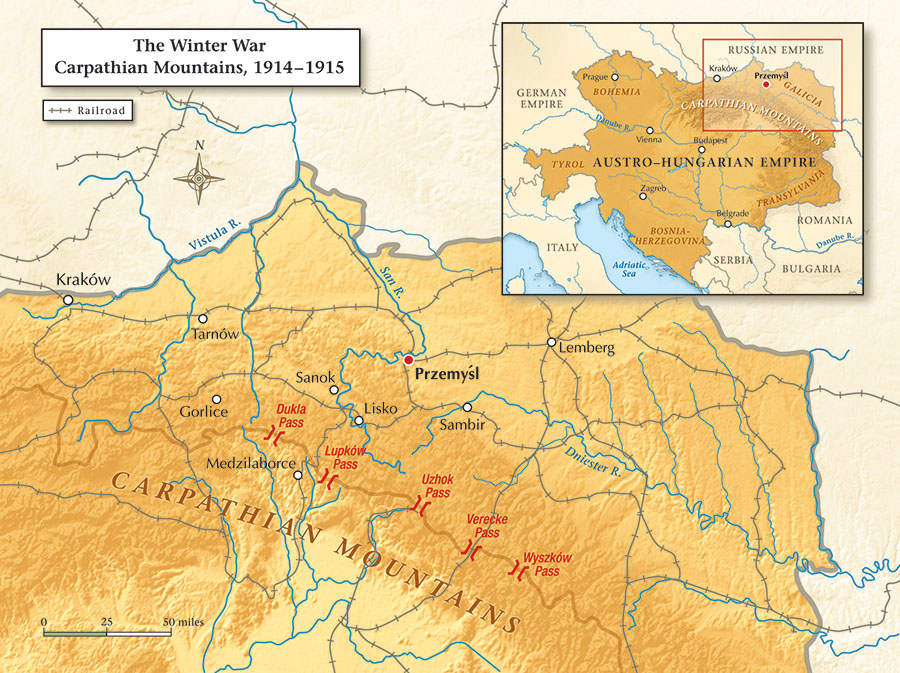

Przemyśl’s siege is a pivotal episode of the war that influenced some key events that succeeded it. Lasting a total of 181 days, the longest siege of the first world war in Europe, the defence of the fortress was commanded by the experienced General Hermann Kusmanek von Burgneustädten (Kusmanek for short). Located along the river San and at the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains, the city is an opening into the Great Hungarian plain through the Łupków, Dukla and Uzsok passes. What's more, it lies at the heart of the south and east-west rail links of Galicia, making it a vital artery for troop and supply mobilisation. All these logistical realities contributed to Przemyśl being chosen as an ideal location for building a modern fort.

The book begins by giving an elaborate history of Przemyśl from medieval times to the early 20th century. The most significant part in the context of this book’s scope is perhaps the city’s history from the middle of the 19th century onwards. Przemyśl’s origins as a site for modern fortification began during the Crimean War (October 16, 1853 - March 30, 1856). Although, it has to be said, most of the work done on it was cursory until 1878. Plans to build a stellar fortress were discussed on and off, depending on the Habsburg Empire’s relations with Russia. By 1914 however, the fortress was rendered mostly obsolete owing to the advances with regard to artillery technology in the intervening years.

The subsequent chapters chronicle the role Przemyśl played in the early days of the war. After the humbling defeats the dual monarchy suffered in 1914, they needed some respite to reorganize and perhaps coordinate their army’s movement with the Germans. For this, they desperately needed time. Thus, Przemyśl became the last hope in delaying the pursuing Russian army. By the time the Russians arrived for the first time, there were 131,000 inhabitants and 21,000 horses within the fortress. Kusmanek found the lack of cooperation between battalions of different nationalities, a huge hindrance. The garrison was made up of mostly third-line Landsturm and honvéd units that were far less equipped and trained than the Common Army.

Watson goes into the design of the forts in some detail. His admirable writing extends to capturing the ethnic tensions within the garrison, disregard for civilian lives, the harrowing realities of daily life for the occupants, the improvisation and ingenuity of civilians and soldiers, the final demolition plans before surrendering, the brutal administration of the city under Russian occupation, return to Habsburg rule in June 1915 and eventual hand over of the city to the newly formed Polish Republic in 1918. For some reason or other, the relief operation of the siege by the joint German and Austro-Hungarian armies is not covered as extensively as the other phases.

Przemyśl’s surrender in March 1915 was highly consequential. In St. Petersburg, it brought about hope that the war in Eastern Galicia would end soon. In Austria-Hungary, the narrative was one of an honourable defeat that nonetheless inflicted a massive loss to the Russian army. Contradicting their earlier assertions, Viennese newspapers now played down the strategic importance of Przemyśl. A month after the fortress fell, Italy, who had been neutral thus far, would join the Entente alliance, sensing Austria-Hungary’s increasing fragility. This would add an enormously bloody front to the already excruciating war.

Preservation of the fortress, despite the huge damage it suffered after the war, has left an imposing ruin. Today statues, cemeteries, memorials and a museum portray the shared pool of memories, lores and importance of Przemyśl and its association with the Great War. On the excellent YouTube channel The Great War, there is a video here of the tour of present day Przemyśl that gives a clearer visual portrait of the fortress.

Watson’s writing is targeted towards the upper-intermediate history reader, and as such it’s a relatively effortless read while maintaining a credible scholarly standard. It’s written with the consultation of archival sources from Poland, Hungary, Austria, Ukraine and Russia as well as published primary sources, secondary sources and unpublished dissertations. The appendices at the end of the book are helpful for readers who might not be familiar with the Eastern Front of the first world war. Moreover, there are an abundance of pictures and maps that capture the Przemyśl of the Great War. As a historian primarily focused on Austria-Hungary, Watson’s sources naturally gravitate towards Habsburg points of view. Although there are discussions of sentiments and accounts from a Russian angle, I still would’ve liked to see a bit more.