Scan barcode

Reviews

The Fortress: The Siege of Przemyśl and the Making of Europe's Bloodlands by Alexander Watson

abehab's review against another edition

4.0

‘’These peasant soldiers are in death, as in life, anonymous. The empires for which they fell would within just a few years both lie in ruins. Yet the violence unleashed by their war would live on.’'

As far as an amateur history enthusiast, such as myself, is concerned, reading a book written exclusively about a besieged fortress city on the Eastern Front of the first world war is as niche as it gets. I have been intrigued with the history of the siege of Przemyśl, ever since I read my first book on the first world war. In the ensuing years, I read a lot on it, but never dipped into a book solely dedicated to the siege. [b:The Fortress: The Great Siege of Przemysl|52971649|The Fortress The Great Siege of Przemysl|Alexander Watson|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1571267227l/52971649._SX50_SY75_.jpg|68162194], marks the first book I read, primarily written on Przemyśl during the first world war.

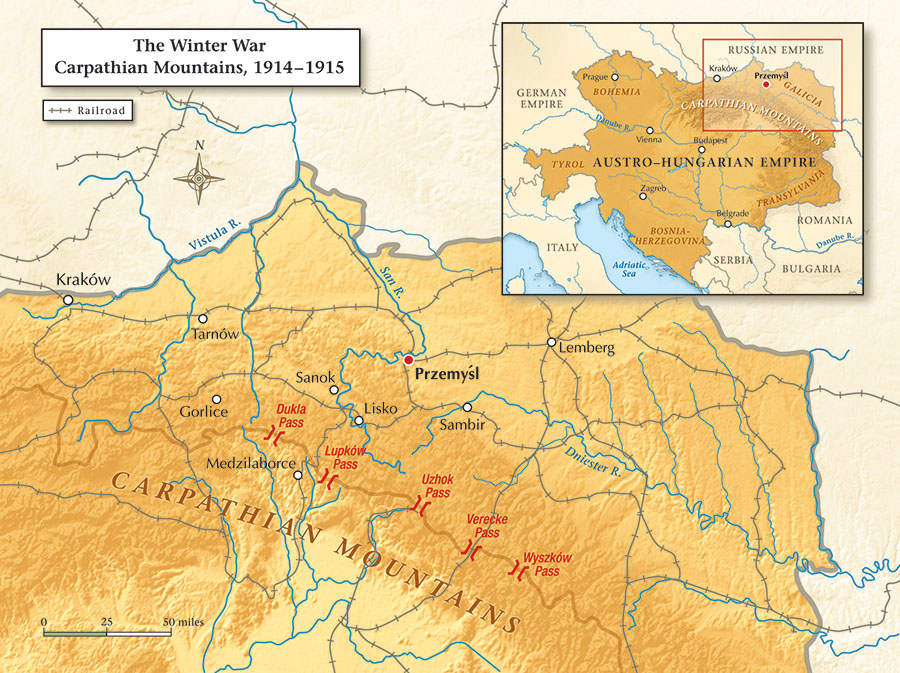

Przemyśl was the third-largest fortress city in The Austria-Hungary Empire, after Kraków and Lemberg (Current day Lviv, Ukraine). The siege of Przemyśl, can in actuality be viewed in three separate phases. The First phase (September 18, 1914 - October 9, 1914) is a failed siege by the Russians on the fortress. The Second phase (November 6, 1914 - March 2, 1915) is the longest and much more successful siege undertook by the Tsar’s army. The third and final phase (May 18, 1915 - June 3, 1915) was the relief operation the joint forces of German and Habsburg armies took up against the Russian occupying forces.

Przemyśl’s siege is a pivotal episode of the war that influenced some key events that succeeded it. Lasting a total of 181 days, the longest siege of the first world war in Europe, the defence of the fortress was commanded by the experienced General Hermann Kusmanek von Burgneustädten (Kusmanek for short). Located along the river San and at the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains, the city is an opening into the Great Hungarian plain through the Łupków, Dukla and Uzsok passes. What's more, it lies at the heart of the south and east-west rail links of Galicia, making it a vital artery for troop and supply mobilisation. All these logistical realities contributed to Przemyśl being chosen as an ideal location for building a modern fort.

The book begins by giving an elaborate history of Przemyśl from medieval times to the early 20th century. The most significant part in the context of this book’s scope is perhaps the city’s history from the middle of the 19th century onwards. Przemyśl’s origins as a site for modern fortification began during the Crimean War (October 16, 1853 - March 30, 1856). Although, it has to be said, most of the work done on it was cursory until 1878. Plans to build a stellar fortress were discussed on and off, depending on the Habsburg Empire’s relations with Russia. By 1914 however, the fortress was rendered mostly obsolete owing to the advances with regard to artillery technology in the intervening years.

The subsequent chapters chronicle the role Przemyśl played in the early days of the war. After the humbling defeats the dual monarchy suffered in 1914, they needed some respite to reorganize and perhaps coordinate their army’s movement with the Germans. For this, they desperately needed time. Thus, Przemyśl became the last hope in delaying the pursuing Russian army. By the time the Russians arrived for the first time, there were 131,000 inhabitants and 21,000 horses within the fortress. Kusmanek found the lack of cooperation between battalions of different nationalities, a huge hindrance. The garrison was made up of mostly third-line Landsturm and honvéd units that were far less equipped and trained than the Common Army.

Watson goes into the design of the forts in some detail. His admirable writing extends to capturing the ethnic tensions within the garrison, disregard for civilian lives, the harrowing realities of daily life for the occupants, the improvisation and ingenuity of civilians and soldiers, the final demolition plans before surrendering, the brutal administration of the city under Russian occupation, return to Habsburg rule in June 1915 and eventual hand over of the city to the newly formed Polish Republic in 1918. For some reason or other, the relief operation of the siege by the joint German and Austro-Hungarian armies is not covered as extensively as the other phases.

Przemyśl’s surrender in March 1915 was highly consequential. In St. Petersburg, it brought about hope that the war in Eastern Galicia would end soon. In Austria-Hungary, the narrative was one of an honourable defeat that nonetheless inflicted a massive loss to the Russian army. Contradicting their earlier assertions, Viennese newspapers now played down the strategic importance of Przemyśl. A month after the fortress fell, Italy, who had been neutral thus far, would join the Entente alliance, sensing Austria-Hungary’s increasing fragility. This would add an enormously bloody front to the already excruciating war.

Preservation of the fortress, despite the huge damage it suffered after the war, has left an imposing ruin. Today statues, cemeteries, memorials and a museum portray the shared pool of memories, lores and importance of Przemyśl and its association with the Great War. On the excellent YouTube channel The Great War, there is a video here of the tour of present day Przemyśl that gives a clearer visual portrait of the fortress.

Watson’s writing is targeted towards the upper-intermediate history reader, and as such it’s a relatively effortless read while maintaining a credible scholarly standard. It’s written with the consultation of archival sources from Poland, Hungary, Austria, Ukraine and Russia as well as published primary sources, secondary sources and unpublished dissertations. The appendices at the end of the book are helpful for readers who might not be familiar with the Eastern Front of the first world war. Moreover, there are an abundance of pictures and maps that capture the Przemyśl of the Great War. As a historian primarily focused on Austria-Hungary, Watson’s sources naturally gravitate towards Habsburg points of view. Although there are discussions of sentiments and accounts from a Russian angle, I still would’ve liked to see a bit more.

mike_baker's review against another edition

5.0

A true story from World War One about which I knew nothing, this is a riveting account of Przemsyl, the Galician fortress that found itself on the front line of the Austro-Hungarian Empire when Russia attacked. A multi-ethnic location held together under the loose alliance of nationalities that were gathered within the Habsburg dominions, the account tells of how its relative harmony was shattered by the privations of war, the successful battle for its defence (an incompetently led defence force seeing off an arguably more incompetent set of attackers) and the Russian siege.

The latter contains all the juicy details of privations you could ever wish to read. People are forced to go hungry, eat horses and just about anything that's even vaguely nutritious, while waiting for a relief army that never arrives and facing the inevitability of being overthrown. Desperate times result in an all-too typical resort to committing atrocities against certain ethnic groups, the city's Jewish communities as always coming under attack. Przemsyl is never the same again. Things seem as though they can't get any worse, and then they do exactly that.

It isn't an overly long book, and Mr Watson has produced a fascinating tale, focusing in on what was no doubt one of many barely remembered communities that showed new frontiers in suffering during wartime. It's an important read.

The latter contains all the juicy details of privations you could ever wish to read. People are forced to go hungry, eat horses and just about anything that's even vaguely nutritious, while waiting for a relief army that never arrives and facing the inevitability of being overthrown. Desperate times result in an all-too typical resort to committing atrocities against certain ethnic groups, the city's Jewish communities as always coming under attack. Przemsyl is never the same again. Things seem as though they can't get any worse, and then they do exactly that.

It isn't an overly long book, and Mr Watson has produced a fascinating tale, focusing in on what was no doubt one of many barely remembered communities that showed new frontiers in suffering during wartime. It's an important read.

matteo_of_eld's review

dark

reflective

tense

medium-paced

2.0

Alexander Watson hates slavs. He is deeply mistrustful and fearful of them. Watson is never not reliving the Cold War. 30 years later, his obsession has led him to writing a book that (ironically, given the subject matter and at least the lip-service paid to the evils of ethnic tension and racial bias) argues that the very nature of the slavic people is to be monstrous, that they have betrayal and self-serving murder deep in their bones, their blood.

"The Fortress" sets as its focus and backdrop the fortress city of Przemysl on the eve and in the first 8 months of World War One. It details the 2 separate sieges the Tsarist Russian army perpetuates against the fortress, and the fighting, starvation, paranoia, and racially-motivated purges and murders that took place both in Przemysl and the surrounding countryside of Galicia (now largely modern day Poland with some chunks in Ukraine.) Devotedly researched and lavishly detailed, Watson uses a mixture of statistics, statistical analyses, and not a small amount of misleading statements and hyperbole to heighten the drama and tension he is recounting. With regard to this Primary Focus- that is, the sieges of Przemysl and the hardship the civilians and defenders endured- "The Fortress" is an engaging and edifying read.

But "The Fortress" has subtitle, and this subtitle betrays Watson's real thesis, the one whose arguments are largely crunched into two measly half chapters and haphazardly scattered around when the narrative allows. "The Making of Europe's Bloodlands."

Watson's real drive with this book is less an account of the siege and more about the racial divides and ethnic cleansing perpetrated in the region, generally referred to in the text (and hereafter in this review) as East Central Europe. Watson's thesis is this: that the ethnic cleansing and hate crimes committed against both the Jews and Ruthenes (Ukrainians) of Galicia (and to a lesser extent the Poles) in the opening months of the war, from Fall 1914 into Summer 1915, presaged the greater and more horrific purges that would be inflicted on Poland and Ukraine during World War Two.

This is heavy subject matter, and as always when reading such things it's important to examine the author's intent, biases, the language used. Watson provides ample opportunity and evidence with which to do so, and frankly it's pretty damning. Right off the bat, Watson reveals his particular biases towards the elite, the "bourgeoisie." I part this is obviously because many of the records he had access to were written by people of this class. Yet, it goes beyond lush depictions of the lives they led and the hardships they endured. Watson is careful to never judge, to always quietly excuse, to never paint with a broad brush even when the elite are obviously complicit in the suffering unleashed on the fortress. This becomes even more obvious when Watson talks about the lower classes, the poor and peasantry. This he does by oscillating between crass pity, cold disdain, and a fair amount of patronizing. To Watson, this rabble are often just mouths to feed and casualties to tally. And of course, brave troop-respecter that he is, Watson is careful to always separate the soldiery from them. Whatever deprivation the civilian population was suffering, the soldiers obviously had it worse. Even the poorest, stupidest, oldest soldier of Austria-Hungary has more value to Watson than single civilian (unless that Civilian is part of the intelligentsia or has some amount of wealth to them.)

Watson reveals even more biases, the real crux of the matter, when he talks about the myriad peoples of the Hapsburg Empire. Austrians (germans) and Hungarians are the civilized outsiders to the region, brought their by the needs of the war. They observe the alien behavior of the "lesser" peoples of the empire from their place of prominence. They rarely commit atrocities, and when they do Watson allows them to hide behind "paranoia", puts them at a remove thanks to their coming from more civilized parts of the empire. In contrast the slavs- the Poles, Ruthenes (Ukrainians) and eventually the Russians) are shown as barely able to contain their barbarity. They commit atrocities and they do so with bare provocation, often because of low-minded nationalist ideals i.e., that only Poles can trust Poles etc etc.

This is where Watson begins seeding the idea that slavs are always chaotic evil. Unlike the noble germans and Hungarians, who take action through some kind of logic the people of Galicia are superstitious, backwards, and willing to be cowed by those above them. The Austrians and Hungarians increasingly distrust their slavic soldiery, and rather than attempt to examine how foolish this was, Watson instead depicts touching and human scenes of solidarity (Russians giving the defenders gifts on Christmas; Russians and their Polish/Ruthene enemies laying down their arms and digging up potatoes together in no-man's land to stave off hunger) as deeply sinister.

Russians in particular get the hilarious (and not to mention pseudo-fascist) portrayal as being dangerous, hypercompetent, bloodthirsty villains that also can't seem to win a lasting victory against the fortress, have armies full of even more ill-equipped and undertrained militia, and are wholly unprepared for assaulting the formidable city. Here is where Watson lays the hyperbole on thick, as he erroneously claims several times that the Russians are the most powerful army in Europe, a statement he repeatedly disproves with no hint of irony. Indeed, Watson seems unaware that the actual text appears to show any Russian victory has more to do with Hapsburg incompetence across the board (not just with the imbecilic Austrian head of war Conrad.) And of course, while Watson sidesteps this for the purpose of the drama, anyone with cursory knowledge of WW1 can tell you that for the majority of the war Germany found itself fighting (and fairly often winning) on 3 fronts, including against Russia.

When the capital G Germans finally show up in the summer of 1915, they are portrayed as ubermensch superheroes. They are polite, they pay for everything (unlike the slavs who are shown perpetually robbing each other and the civilians who they are supposed to protect) and they awe everyone around them. Intentionally and provocatively, Watson evokes Nazi imagery as he describes a scene of German soldiers goose-stepping on parade to cheering crowds.

As for the Jews of the tale, Watson always goes above and beyond to depict them as the ultimate victims of the violence being committed on both sides. He's careful to provide statistics and to show evidence that whatever the hateful slavs believe about the Jews they live alongside, these beliefs are not justified. Even here, however, Watson's biases cannot be avoided. He time and again focuses more on the hardships suffered by the wealthiest Jews- again Watson has already revealed his sympathies towards those with capital above those without- and this is further colored by the way Watson uses racial depictions. Curiously, when considering the specific Jews he centers on and his portrayal of the nietzschean Germans, one can't help but think Watson doth protest too much. What is his angle here? Is it really to discuss the horrific anti-Semitism, or does this fall within the typical (and distinctly English) neoliberal fashion of claiming to be against anti-Semitism while perpetuating systemic abuses and quietly admiring the Germany of the first half of the 21st century?

Again, Watson does not seem to be over the Cold War. In the first half-chapter where he outlines his thesis on the so-called Bloodlands, Watson describes the Tsarist policy of ethnic cleansing that they unleash on occupied Galicia, largely with the intent of driving out Jews, forcefully absorbing Ruthenes as "Little Russians", switching the language of school, business, and government to Russian, and converting all to Russian Orthdoxy. Watson is careful to clarify that this Tsarist cleansing is not nearly as brutal and inhumane as later purges would be. Even still, much of the cleansing is depicted as being helped (or at the very least unhindered) by the other slavs of East Central Europe, who are all more than happy to sit idly by and wait for a chance to take advantage of their Jewish neighbors. Even as Ruthenes and Poles feel no national solidarity with the Russians, Watson seems to indicate that this hardly matters when solidarity against a perceived enemy is on the table.

In the Epilogue, where the other half-chapter dedicated to this thesis lies, Watson brings it all home and truly lays his cards on the table. At the end of WW1, what do the Ruthenes and Poles do with their newfound freedom but unleash bloody civil war against each other; why wouldn't they considering their slavic blood? When now-Poland is divided in half (and neatly so is Przemysl) by the Nazis and Stalinist Soviets, the book posits this is old hat. There's already been decades of death and destruction, what's a few years more?

Importantly for Watson, this sets the stage for the grand finale of his thesis. After stating that the Nazis and Soviets were the "evil empires of Europe" (outdated at best and revealing of Watson's ideological predilections), Watson once again begins doing his darnedest to throw slavs under the bus. In this case, Soviet-occupied Poland is a horror show where the Russians again impose the Russian language on all, absorb the slavs as they can, supposedly commit 500,000 murders against ideological opponents and (to Watson, worst of all) land and property is once again redistributed from the wealthy to the destitute. Watson erroneously claims that those 500k deaths in particular are worse than anything the Nazis did in East Central Europe. In this way he for some reason sets the stage to downplay the horror of the Nazi occupation.

And a few paragraphs later again disproves his own statement when he describes the tens of thousands of murders that took place when the Nazis first occupied the region, the tens of thousands (if not hundreds of thousands) more as the Nazis began Operation Barbarossa and invaded Soviet territory, and then acknowledges that approximately 475,ooo Jews from East Central Europe were carted to just one death camp in Poland (implying but never outright stating that more were carted to other death camps, and that many other "undesirables" were also victimized in this way beyond Jews.) Anyone with a single brain cell and a calculator can tell you that those numbers indicate far worse atrocities committed by the Nazis. And yet Watson insists on this contest, and on painting the Soviets as more heinous, more vile.

He drives this point home by finally casting the Russians (and slavs in general) as the ultimate true villain by drawing direct parallels between the Tsarist policy of ethnic cleansing and the later Nazi one. While he does walk this back and makes it clear he's not claiming the Nazis were inspired by the Russians, his comparison is once again intentionally provocative. Watson's vendetta must be satisfied, and he must at all costs show that slavs are evil, the true evil of Europe and possibly the world. He's not over the Cold War.

As a coda to this review, I also want to draw attention to the way Watson views socialism and communism. As should be obvious when reading the above, Watson is clearly someone who believes in the laughably false claims of the Victims of Communism organization. He begins by describing the Bolshevik revolution with a hilarious and frankly embarrassing vitriol; in fearful language he decries the "horrific" socialist policy of appropriating ill-gotten wealth, land, property from the rich industrialists and autocrats of the collapsing Russian empire; the takeover of industry by the worker; the establishment of public housing and a social safety net. Watson, a slave of capitalism and a true end-of-history neoliberal, shows how afraid he is of the power of caring for others... what could be more evil than that? Why of course the hated slav.

"The Fortress" sets as its focus and backdrop the fortress city of Przemysl on the eve and in the first 8 months of World War One. It details the 2 separate sieges the Tsarist Russian army perpetuates against the fortress, and the fighting, starvation, paranoia, and racially-motivated purges and murders that took place both in Przemysl and the surrounding countryside of Galicia (now largely modern day Poland with some chunks in Ukraine.) Devotedly researched and lavishly detailed, Watson uses a mixture of statistics, statistical analyses, and not a small amount of misleading statements and hyperbole to heighten the drama and tension he is recounting. With regard to this Primary Focus- that is, the sieges of Przemysl and the hardship the civilians and defenders endured- "The Fortress" is an engaging and edifying read.

But "The Fortress" has subtitle, and this subtitle betrays Watson's real thesis, the one whose arguments are largely crunched into two measly half chapters and haphazardly scattered around when the narrative allows. "The Making of Europe's Bloodlands."

Watson's real drive with this book is less an account of the siege and more about the racial divides and ethnic cleansing perpetrated in the region, generally referred to in the text (and hereafter in this review) as East Central Europe. Watson's thesis is this: that the ethnic cleansing and hate crimes committed against both the Jews and Ruthenes (Ukrainians) of Galicia (and to a lesser extent the Poles) in the opening months of the war, from Fall 1914 into Summer 1915, presaged the greater and more horrific purges that would be inflicted on Poland and Ukraine during World War Two.

This is heavy subject matter, and as always when reading such things it's important to examine the author's intent, biases, the language used. Watson provides ample opportunity and evidence with which to do so, and frankly it's pretty damning. Right off the bat, Watson reveals his particular biases towards the elite, the "bourgeoisie." I part this is obviously because many of the records he had access to were written by people of this class. Yet, it goes beyond lush depictions of the lives they led and the hardships they endured. Watson is careful to never judge, to always quietly excuse, to never paint with a broad brush even when the elite are obviously complicit in the suffering unleashed on the fortress. This becomes even more obvious when Watson talks about the lower classes, the poor and peasantry. This he does by oscillating between crass pity, cold disdain, and a fair amount of patronizing. To Watson, this rabble are often just mouths to feed and casualties to tally. And of course, brave troop-respecter that he is, Watson is careful to always separate the soldiery from them. Whatever deprivation the civilian population was suffering, the soldiers obviously had it worse. Even the poorest, stupidest, oldest soldier of Austria-Hungary has more value to Watson than single civilian (unless that Civilian is part of the intelligentsia or has some amount of wealth to them.)

Watson reveals even more biases, the real crux of the matter, when he talks about the myriad peoples of the Hapsburg Empire. Austrians (germans) and Hungarians are the civilized outsiders to the region, brought their by the needs of the war. They observe the alien behavior of the "lesser" peoples of the empire from their place of prominence. They rarely commit atrocities, and when they do Watson allows them to hide behind "paranoia", puts them at a remove thanks to their coming from more civilized parts of the empire. In contrast the slavs- the Poles, Ruthenes (Ukrainians) and eventually the Russians) are shown as barely able to contain their barbarity. They commit atrocities and they do so with bare provocation, often because of low-minded nationalist ideals i.e., that only Poles can trust Poles etc etc.

This is where Watson begins seeding the idea that slavs are always chaotic evil. Unlike the noble germans and Hungarians, who take action through some kind of logic the people of Galicia are superstitious, backwards, and willing to be cowed by those above them. The Austrians and Hungarians increasingly distrust their slavic soldiery, and rather than attempt to examine how foolish this was, Watson instead depicts touching and human scenes of solidarity (Russians giving the defenders gifts on Christmas; Russians and their Polish/Ruthene enemies laying down their arms and digging up potatoes together in no-man's land to stave off hunger) as deeply sinister.

Russians in particular get the hilarious (and not to mention pseudo-fascist) portrayal as being dangerous, hypercompetent, bloodthirsty villains that also can't seem to win a lasting victory against the fortress, have armies full of even more ill-equipped and undertrained militia, and are wholly unprepared for assaulting the formidable city. Here is where Watson lays the hyperbole on thick, as he erroneously claims several times that the Russians are the most powerful army in Europe, a statement he repeatedly disproves with no hint of irony. Indeed, Watson seems unaware that the actual text appears to show any Russian victory has more to do with Hapsburg incompetence across the board (not just with the imbecilic Austrian head of war Conrad.) And of course, while Watson sidesteps this for the purpose of the drama, anyone with cursory knowledge of WW1 can tell you that for the majority of the war Germany found itself fighting (and fairly often winning) on 3 fronts, including against Russia.

When the capital G Germans finally show up in the summer of 1915, they are portrayed as ubermensch superheroes. They are polite, they pay for everything (unlike the slavs who are shown perpetually robbing each other and the civilians who they are supposed to protect) and they awe everyone around them. Intentionally and provocatively, Watson evokes Nazi imagery as he describes a scene of German soldiers goose-stepping on parade to cheering crowds.

As for the Jews of the tale, Watson always goes above and beyond to depict them as the ultimate victims of the violence being committed on both sides. He's careful to provide statistics and to show evidence that whatever the hateful slavs believe about the Jews they live alongside, these beliefs are not justified. Even here, however, Watson's biases cannot be avoided. He time and again focuses more on the hardships suffered by the wealthiest Jews- again Watson has already revealed his sympathies towards those with capital above those without- and this is further colored by the way Watson uses racial depictions. Curiously, when considering the specific Jews he centers on and his portrayal of the nietzschean Germans, one can't help but think Watson doth protest too much. What is his angle here? Is it really to discuss the horrific anti-Semitism, or does this fall within the typical (and distinctly English) neoliberal fashion of claiming to be against anti-Semitism while perpetuating systemic abuses and quietly admiring the Germany of the first half of the 21st century?

Again, Watson does not seem to be over the Cold War. In the first half-chapter where he outlines his thesis on the so-called Bloodlands, Watson describes the Tsarist policy of ethnic cleansing that they unleash on occupied Galicia, largely with the intent of driving out Jews, forcefully absorbing Ruthenes as "Little Russians", switching the language of school, business, and government to Russian, and converting all to Russian Orthdoxy. Watson is careful to clarify that this Tsarist cleansing is not nearly as brutal and inhumane as later purges would be. Even still, much of the cleansing is depicted as being helped (or at the very least unhindered) by the other slavs of East Central Europe, who are all more than happy to sit idly by and wait for a chance to take advantage of their Jewish neighbors. Even as Ruthenes and Poles feel no national solidarity with the Russians, Watson seems to indicate that this hardly matters when solidarity against a perceived enemy is on the table.

In the Epilogue, where the other half-chapter dedicated to this thesis lies, Watson brings it all home and truly lays his cards on the table. At the end of WW1, what do the Ruthenes and Poles do with their newfound freedom but unleash bloody civil war against each other; why wouldn't they considering their slavic blood? When now-Poland is divided in half (and neatly so is Przemysl) by the Nazis and Stalinist Soviets, the book posits this is old hat. There's already been decades of death and destruction, what's a few years more?

Importantly for Watson, this sets the stage for the grand finale of his thesis. After stating that the Nazis and Soviets were the "evil empires of Europe" (outdated at best and revealing of Watson's ideological predilections), Watson once again begins doing his darnedest to throw slavs under the bus. In this case, Soviet-occupied Poland is a horror show where the Russians again impose the Russian language on all, absorb the slavs as they can, supposedly commit 500,000 murders against ideological opponents and (to Watson, worst of all) land and property is once again redistributed from the wealthy to the destitute. Watson erroneously claims that those 500k deaths in particular are worse than anything the Nazis did in East Central Europe. In this way he for some reason sets the stage to downplay the horror of the Nazi occupation.

And a few paragraphs later again disproves his own statement when he describes the tens of thousands of murders that took place when the Nazis first occupied the region, the tens of thousands (if not hundreds of thousands) more as the Nazis began Operation Barbarossa and invaded Soviet territory, and then acknowledges that approximately 475,ooo Jews from East Central Europe were carted to just one death camp in Poland (implying but never outright stating that more were carted to other death camps, and that many other "undesirables" were also victimized in this way beyond Jews.) Anyone with a single brain cell and a calculator can tell you that those numbers indicate far worse atrocities committed by the Nazis. And yet Watson insists on this contest, and on painting the Soviets as more heinous, more vile.

He drives this point home by finally casting the Russians (and slavs in general) as the ultimate true villain by drawing direct parallels between the Tsarist policy of ethnic cleansing and the later Nazi one. While he does walk this back and makes it clear he's not claiming the Nazis were inspired by the Russians, his comparison is once again intentionally provocative. Watson's vendetta must be satisfied, and he must at all costs show that slavs are evil, the true evil of Europe and possibly the world. He's not over the Cold War.

As a coda to this review, I also want to draw attention to the way Watson views socialism and communism. As should be obvious when reading the above, Watson is clearly someone who believes in the laughably false claims of the Victims of Communism organization. He begins by describing the Bolshevik revolution with a hilarious and frankly embarrassing vitriol; in fearful language he decries the "horrific" socialist policy of appropriating ill-gotten wealth, land, property from the rich industrialists and autocrats of the collapsing Russian empire; the takeover of industry by the worker; the establishment of public housing and a social safety net. Watson, a slave of capitalism and a true end-of-history neoliberal, shows how afraid he is of the power of caring for others... what could be more evil than that? Why of course the hated slav.

More...